How to Successfully Coexist with Your Annoying Roommate!

Living with roommates can be an eye-opening experience. As the saying goes, "You don't know someone until you live with...

Read More

UK University Life and Mental Health: Getting Help

University life can be a rollercoaster ride. Alongside the joys of coursework and exams, you also have to deal with...

Read More

How to Choose a Student Bank Account

Hey there, future uni student! So, you've got everything sorted for your grand university adventure—uni choices, accommodation, and even a...

Read More

8 Tips to Manage Time Better: College Life

We all know that college can be a stressful time. You've got classes to attend, exams to study for, friends...

Read More

11 Things You Need to Know About Doing a Postgrad Course

First things first, you need to figure out why you want to pursue a postgrad in the first place. Having...

Read More

10 Things You Need to Know Before Joining University

You’ve slogged your way through secondary school and managed to achieve the necessary grades for your chosen university. What a...

Read More

What International Students Can Expect in the UK

Hey there! So, you’re thinking about studying in the UK, huh? Well, let me tell you, despite the infamous drizzle,...

Read More

Moving In to Your Student Home – Tips and Hacks

Moving into your student home is an exciting milestone, but the process of actually moving in can be stressful and...

Read More

Use of AI to Write Assignments, Is it Worth It?

Since it was first developed in November 2022, ChatGPT has taken the academic world by storm. In this digital age,...

Read More

Protected Health Information (PHI): Privacy, Security, and Confidentiality Best Practices

Assessment 2 Instructions: Protected Health Information (PHI): Privacy, Security, and Confidentiality Best Practices Content Prepare a 2-page interprofessional staff update on...

Read More

Managing Health Information and Technology

Welcome to your Capella University online course, NURS-FPX4040 - Managing Health Information and Technology Nursing informatics (NI) is a growing...

Read More

ABC Healthcare Corporation

Part 1 Introduction This assignment builds on your prior work in the Units 2 and 6 assignments. It is...

Read More

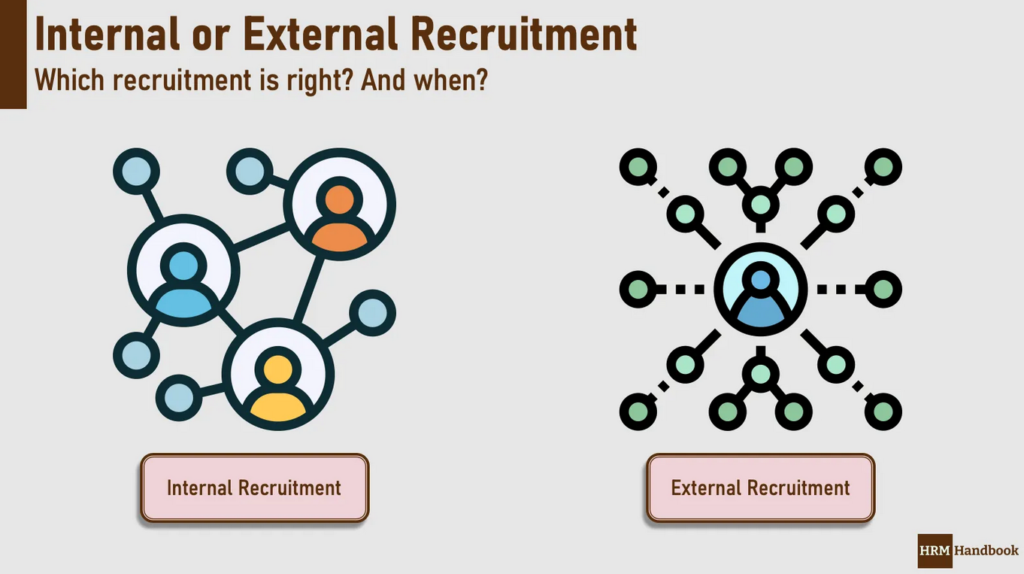

HR Challenge: Selecting the Right Candidate (Internal – External)

HR Challenge: Selecting the Right Candidate (Internal - External) Prepare a 3-4 page analysis considering several possible courses of action...

Read More

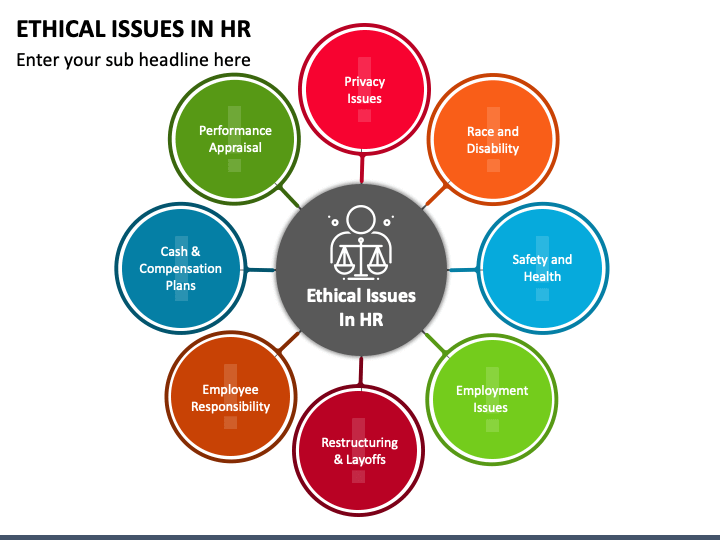

HR Challenge: A Question of Ethics

The other internal employee is the best qualified young man with over eight years in the company. He holds multiple...

Read More

Employing Capital Budgeting and Risk

Part A Employing Capital Budgeting and Risk These resources will help you to complete this discussion: Nockolas, S. (2015). How...

Read More

U.S. steel manufacturers will be able to maintain its competitiveness by the tariff

For your arguments, remember to be logical, specific, practical, and justifiable. Remember to cite any sources from...

Read More

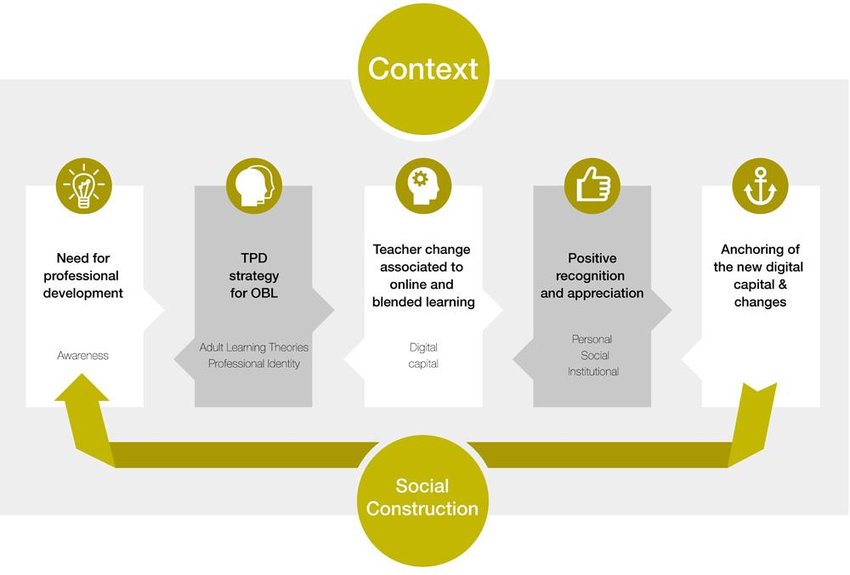

Digital Awareness and Professional Development

Faculty of Business and Law Assignment Brief Unit Title: Digital Awareness and Professional Development Unit Code: 5S4Z1000(2) Core: Yes Level:...

Read More