Significance Of Kantian Imperatives To Assess Moral Acts Philosophy – Immanuel Kant Essay

In Section II of Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant explains the capacity of will as practical reason–the ability to cause actions according to principles the agent represents to himself. For rational beings with the kind of will we have–one which does not automatically will in accord with reason–principles thought of as applying to the will objectively as a matter of rationality are represented in the form of imperatives. Kant draws a distinction between two kinds of imperatives: hypothetical and categorical. This paper is intended to identify the basic frameworks within which Kantian understandings of morality could be positioned and figured out logically. It also, somewhat critically, attempts to see how Kant envisages universalisable nature of moral acts and how this could be applied to definite situations. For instance there is a clear relation between reason or wills and moral and/or amoral acts and the natur

The main area of emphasis in this paper is categorical imperative. This paper is divided into four sections including this introduction. In the second section a discussion of hypothetical and categorical imperatives is undertaken in the light of some critical perspectives available. The third section discusses the formula of universal law under the maxim “Act only according to the maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law”. The fourth section undertakes discussion of a specific instance and the fifth section includes my concluding remarks.

Hypothetical and Categorical imperatives – Philosophy on Kant

According to Kant the fundamental principle of morality is an imperative or a command that provides definite direction regarding courses of action to be pursued. According to him:

. . . all imperatives command either hypothetically or categorically. The former present the practical necessity of a possible action as a means to achieving something else which one desires (or which one may possibly desire). The categorical imperative would be one which presented an action as of itself objectively necessary, without regard to any other end. (Kant 1989).

According to this definition the ends of an action determines whether the imperative is hypothetical or categorical. Thus a hypothetical imperative implies an instrumental relation between the means and the ends as is reflected in saying that ‘study well if you want to pass the examination’. Here the action that is, study, is related with the goal of passing in the examination in a conditional sense. On other hand if the action, rather than serving as a means to achieve some other ends, implies an end in itself the imperative is categorical and is a law of morality. That is, Kant, beyond any ambiguity makes the distinction between moral acts and hypothetical imperatives; that, moral acts cannot be seen as instruments to establish relationship with some other material desires or ambitions all of which are “selfish”. It is often noticed that Kant contrasts actions that respects moral laws with actions with some ulterior motive. In the Metaphysics of Morals he clearly states that selfish motives and other similar ends cannot be the starting point for. When human beings act on the basis of some ‘material maxim’ their actions are oriented more towards pleasure and happiness than towards fulfilling the moral laws (Kant 1909 (1788)).

The concept of categorical imperative has emerged as part of the Kantian project to provide a new formulation of morality rather than to create a new one. With regard to hypothetical imperative the only restraint on the will is rather simple and remains in the application of Kant’s ethics of principle “whoever wills the end, wills also the means in his power that are indispensably necessary thereto” (Kant 1989).

The significance of categorical imperative remains in the fact that it provides a criterion by which it is possible for any human being to distinguish with some amount of certainty the moral actions from actions that are amoral. While comparing with hypothetical imperative categorical imperative provides certain difficulties to the extent that it does not depend on any antecedent condition or of any successive end. This necessity unconditionally connects the will with the law. In order to resolve this difficulty Kant suggests considering the conception of a

Apart from the law, the categorical imperative’s only demand is that its maxims should follow and conform to the universal law of morality. Since law contains no conditions to restrict it, in effect, the maxim of the action should conform to a universal law. In other words, the categorical imperative demands that a maxim of one’s action should be universal law. In order to clarify these claims Kant provides four examples of maxims-duties (suicide, false promising, noncultivation of one’s natural talents, and indifference to the misfortune of others- (Kant 1989) and shows how a maxim can be raised to the status of a universal law (ref). I shall discuss this point with a little elaboration in the next sections.

Philippa Foot (2007) challenges such clear cut distinctions made between moral acts and imperatives that are hypothetical. She does so by drawing from the general character of imperatives that assumes that certain acts ‘should be’, ‘ought to be’, or ‘must be’ done, or, in other words, statements with such injunctions. For Kant even an assertion that ‘it would be good to do or refrain from doing’ is an imperative as it has the power of a command of reason (154). Nevertheless even when imperatives are categorical, Foot argues, one may think about the rationality of such actions leaving sufficient space to reserve his decision to or not to follow them. To this is added the important fact that “moral judgments have no better claim to categorical imperatives than do statements about matters of etiquette” (156-157). Although Foot indeed does some reservations for her own critical perspectives regarding Kantian notion of moral acts and imperatives she, nonetheless, concludes that “Kant, in fact, was a psychological hedonist in respect of all actions except those done for the sake of the moral law, and this faulty theory of human nature was one of things that preventing him from seeing that moral virtue might be compatible with the rejection of categorical imperative” (157). She suggests that, though unintentionally, such a view of moral acts could be totally destructive of morality as “no one could ever act morally unless he accepted such considerations as in themselves sufficient reason for action” (157-158).

However Foot’s critique is not without its own loopholes. Take for instance, “answer an invitation in the third person in the third person’ is an imperative of etiquette, and it is not conditional” is an example that Foot deploys to show the difficulty in separating between imperatives concerning matters of morality and etiquette (156). This maxim does not apply to one only on the condition that one has some end that is served by being polite. But from a Kantian perspective this again is not categorical since it does not apply to us simply because we are rational enough to understand and act on it, or simply because we possess a rational will. Imperatives of etiquette apply to us because according to the prevailing customs our being, our presence and our personality are measured and appraised by standards of politeness, whether we accept those standards or not. Hence that provides sufficient condition why an imperative of etiquette should be followed and why such an imperative could not be considered as categorical in a Kantian sense.

This also leads our discussion to the question of reason and rationality as embedded within the complexities of moral, amoral and practical judgments, acts and, above all, imperatives. According to Korsgaard the ‘Will’ that Kant specifies is the practical reason and “since everyone must arrive at the same conclusions in matters of duty, it cannot be the case that what you are able to will is a matter of personal taste or relative to your individual desires” (Korsgaard 2007). For Kant it is the will that undergoes the moral and prudential evaluation of rational requirements than the acts that express the wills. Hence there is a direct equation between the wills or reason and the kind of imperative that commands its direction and functioning. Thus, in the context of categorical imperative, one has to assume that Kant’s presumption about reason and rationality has more to do with a metaphysical sense of reason in the absence of which one will end up with the conclusion that categorical imperative implies a failure of rationality which can never be the case. It is not the failure of rationality to not to opt for the means for the willed ends. As a matter of choice it then deliberately forsakes, or at least does not count on, the ulterior objects of life for some metaphysical principles that we term as moral laws and morality. In his Ground work for the Metaphysics of Morals Kant admits the difficulty “to identify with complete certainty a single case in which the maxim of an action . . . rested solely on moral grounds and on the person’s thought of his duty” (Kant 1989: 14). He repeats his caveat against coming under the trap of believing that we were guided by our sense of duty rather than a secret impulse of self-love masquerading as the idea of duty since we would like “to give ourselves credit for having a more high-minded motive than we actually have” (15).

The Formula of Universal Law

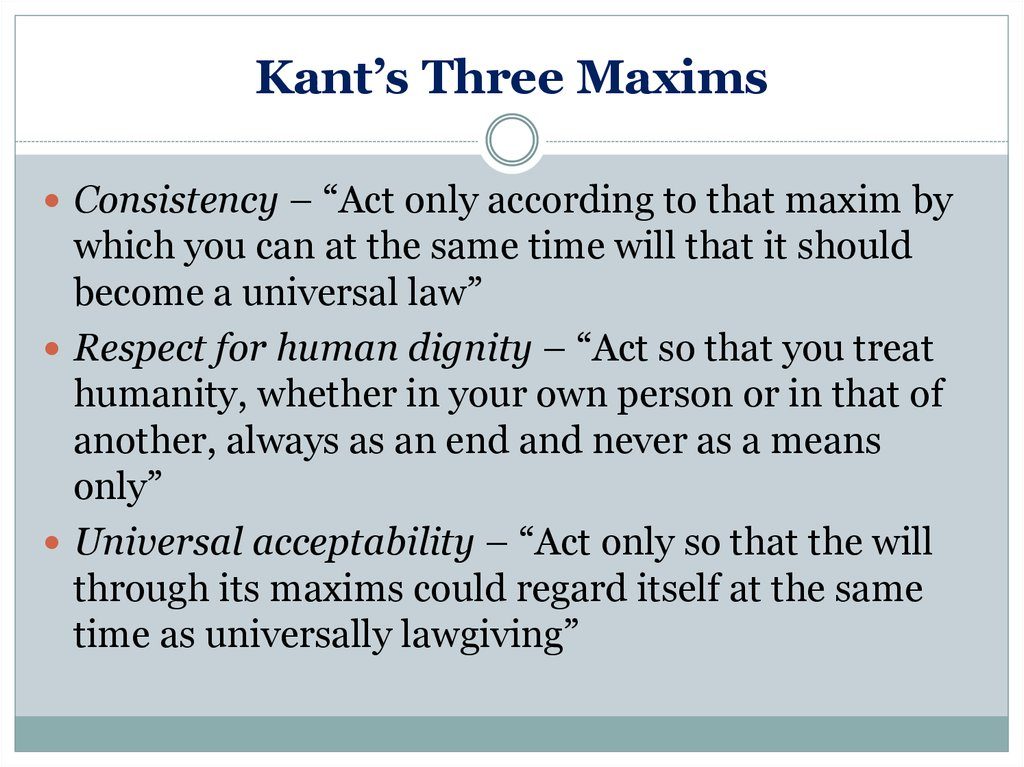

The first formulation of categorical imperative is “Act only according to the maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law”. Implicit in this formulation is the 1) a priori character of categorical imperative, 2) the test of prudence of reason and the wills, and 3) the rational nature of morality. I shall explain these three underlying notions briefly. The a priori nature of the categorical imperative is derived because Kant believes that morality must be based on such a universal law that precedes any simplified or even complex system of logic so that it becomes applicable to everyone regardless of inclination. The testability guarantees that the maxim one is acting upon is a maxim that anyone would have good reason to act on and one has a rational basis for this belief since the maxim could be universalized. This is precisely where the third implicit understanding is derived from that morality, for Kant, is rational so that one can freely give in without concerning too much about its consequences.

According to Korsgaard (2007) Universal Law test helps one to find out if one can will his maxim as a universal law of nature without contradiction. The contradiction he points out can arise in conception and in willing (541-542). She gives three possibilities for a contradiction to arise in this context.

The Logical Contradiction Interpretation arises when the action we are contemplating is the wrong action. Here the universal law is logically impossible and cannot be conceived at all. For Kant it is irrational to perform an action if the maxim behind it contradicts itself once made into a universal law. For instance it would be impossible to make a lying promise to borrow money in a universe where everyone acted on a maxim to make a lying promise to borrow money. The Teleological Contradiction Interpretationarise when we conceive of nature as a teleological system; as a system where organs, instincts or action-types have an end specific to them that is essential to their proper natural functioning. If the maxim contradicts ends of an action-type, organ or instinct, then it forbids the wrong action. The practical contradiction interpretation arises when the maxim describes an action that would be wrong if the universalization of the maxim results in a practical contradiction such that it defeats the purpose of the maxim (Korsgaard 2007: 544).

To provide an example let us consider a merchant who decides to cheat his customers. The maxim under consideration for him, while he makes his choice, is to ‘deceive your customer to make easy profits’. Now as we all know that the merchant is following a wrong principle as it wrong to deceive your customer. Therefore we can assume that an effort to find an apriori principle to justify his inclination is blocked from the beginning. But where does the block emerge from needs be explained apart from finding a replacement that could be universalized for the maxim already in possession. In this context we can clearly see that the person stands amidst the complexity of finding a maxim that could contradict his own inclinations. In other words, in order to overcome the block he needs to replace his maxim with something like ‘it is one’s duty to not to deceive one’s customer’. This in fact provides him a good enough reason to not to engage in practices that goes against his inclinations. Nevertheless the will still remains at a crossroad between principle and inclination in the sense that the former indicates how to reason about the latter. Thus it is not the inclination that provides him sufficient reason to be followed but, on the contrary, it is the principle or maxim that provides him sufficient reason to be followed. In other words his lack of any reason to follow his inclination is sufficient reason not to follow them. “The only reason there can be for the agent to go against all of his inclinations is his very lack of a principle endorsing them as good enough reason to go along” (Kant 1989: 68).

The above example is intended to show how Kant assumes amoral acts and the maxims to follow them cannot become universal laws and thus only moral acts has universal substantiation. That categorical imperative which is unconditional and a priori should also possess the quality of universalisablity. This universalisability of the maxim of categorical imperative, as the example shows, does distinguish immoral actions from the moral ones and proves the difficulty to universalize the reason that may accompany immoral actions.

Now let us consider a problem with determining morality with categorical imperative illustrated by the following example. Imagine that Erick stands to inherit millions of dollars when his grandmother dies, and he will get the money so long as he does nothing immoral. Erick strangles his grandmother, acting on the maxim “Use your own hands to make money.” Now in this instance although the act has the quality of being looked at as immoral on the first onset given the maxim behind it, that is make money with your own hands, it sounds logical and possesses the qualities of categorical imperative. Korsgaard in her article (2007) suggests that if a person formulated a maxim that said ‘if my baby cries constantly at night I will kill it in order to get some sleep’ there would be no logical contradiction involved in universalizing this maxim. She concludes that though “such an action is clearly immoral . . . the logical contradiction interpretation isn’t the best way to interpret the universalization test”.

Now let us see the instance in its full details. Although our initial analysis of the given instance in the light of Korsgaard’s comments sounds logical given the interpretations of categorical imperative and its universal character there seems to be some primary difficulties in arriving at such an easy conclusion. For example, if we go back to the basic definition of categorical imperative as it is given by Kant then we find the primary condition for an imperative to be categorical is its unconditional nature. That it should not be motivated by, nor oriented towards, any ulterior objects in life. Since all material wishes, even those that could be termed as good ones, is related with one’s love for him/her self categorical imperative could be viewed only on the basis of its disorientation with anything that is intended to bring pleasure or happiness in life.

This provides us with another twist to analyze the given instance which is still substantiated by a maxim that could be made a universal law. The difficulty here emerges from the fact that, at least in this instance, we have separated the universal nature of categorical imperative from that of its basic definition. That Korsgaard, just as many others in this context, seems to have arrived at on his conclusion not by looking upon the whole nature of categorical imperative but with reference to the qualities enumerated by Kant himself. In other words an instance cannot be analyzed solely on the basis of the test of universalisability when that instance does not even pass the initial test of what imperative is implicit in that particular instance or act.

In this case although Erick’s action has the backup of the maxim ‘make money with your own hands’ which in turn sounds justified and universal on even moral grounds, the fact that that maxim exhibits a conditional formula connecting definite means with definite ends does not qualify it as categorical imperative and thus cannot be qualified as a moral act according to Kantian perspective. This is applicable to even the example that Korsgaard has given in his article which relates the means that is, killing his baby with the ends, that is, getting good sleep. The imperative in both these instances is hypothetical rather than categorical.

Conclusion

The above arguments show the difficulties and also the possibilities that a Kantian analysis of morality implies. Despite the fallacies often attributed to categorical imperative and the difficulties it presents, the categorical imperative still stands relevant to arrive at conclusions in matters concerning morality. The fact that its explanations, as given by Kant himself, have all possibilities to contradict with each other does not dilute its strength in any sense. The problem, as we already saw in our last example, is more with interpretations of Kant’s own formulations. That any instance cannot be looked at solely from the perspective of any one of the qualities of categorical imperative, rather it should be thoroughly analyzed, weighed, and measured against the fuller complexities, remains a tough exercise even today. But if one were to undertake the task then it is an unquestionable fact that Kantian perspectives, especially that of categorical imperative, still provides a highly potential tool to make judgments with regard to matters of morality.

Read more: ON A SUPPOSED RIGHT TO LIE BECAUSE OF PHILANTHROPIC CONCERNS by Immanuel Kant

You must be logged in to post a comment.